Most of the time, when you hear or read the phrase “Dollar Cost Averaging”, it’s being applied to the stock market. It’s the practice of buying a set amount of stock at a regular interval whereby the average cost per share of stock ends up normalizing. So, if you buy stock high one time, and low the next, and then high, your average cost is going to be lower than the high cost and more than the low cost. So long as the stock doesn’t pull an Enron, and slowly increases in value, you come out ahead in the long term.

But, does it have to apply to just stocks? Absolutely not. It really can apply to anything that you buy on a regular basis. Gas for example. A couple of weeks ago, I filled up the car at about $3.89 a gallon. Today, as I drove by the gas station, it was at $3.69 a gallon. I filled up at $3.89, so I don’t really need any gas right now, but I seriously considered stopping and topping off the tank to bring the overall cost of the gas I bought over the last several weeks down a few pennies.

There might be some argument that dollar cost averaging doesn’t work very well for consumables. After all, if I had bought a few gallons at $3.69, my overall reserves of gas would not increase. I’ve already consumed those few gallons that I paid $3.89 a gallon for. But, I would have increased the total amount I had bought, and the average price would have been less than $3.89.

Dollar cost averaging works especially well for things that regularly fluctuate in price. If you’re building a stockpile of food in your basement, it’s chili bean season. There’s sales all over the place for chili beans. Now, you could buy 50 or so cans at the sale price, but you might be tight on storage space. Or, they might expire before you get to use them all. Instead, you can use dollar cost averaging to buy slightly more than you might normally buy, and bring down the average cost of the ones you have to buy later in the season when they aren’t on sale any more.

Dollar cost averaging works especially well for things that regularly fluctuate in price. If you’re building a stockpile of food in your basement, it’s chili bean season. There’s sales all over the place for chili beans. Now, you could buy 50 or so cans at the sale price, but you might be tight on storage space. Or, they might expire before you get to use them all. Instead, you can use dollar cost averaging to buy slightly more than you might normally buy, and bring down the average cost of the ones you have to buy later in the season when they aren’t on sale any more.

O.K. This does seem a little silly. After all, who’s going to go out and figure out the average cost of a can of chili beans in the basement? But, there’s a point in there. There’s a certain rationality in buying things in set increments over time rather than trying to time the market (or chili bean sale) and buying a whole lot of the item at once. How many times have you bought something only to find that it was on sale the next week?

And, don’t forget that the same principle goes the other way. There are many normal things that we do on an everyday basis that can apply to the stock market too! When we shop, we tend to stick to the brand names we know. Even if those brand names are generic names. Go far enough out of town and stop at a grocery store and try and convince yourself that the generic brand at that store is the same as the generic at home. It takes a bit of thought! Sticking to companies (brands) that you know when investing can be beneficial too. More often than not, those brands and companies are companies that have been around for a long time and built a certain amount of trust in the marketplace. They’re unlikely to just be an overnight sensation, or to quickly fall from favor. In short, they’re stalwart investing options.

What other everyday habits do we all have that can be carried over to the stock market? And what other stock market habits do we have that can carry over to everyday life?

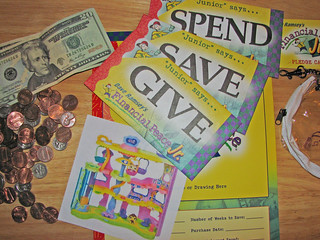

img credit:Nick Harris1, on Flickr

I started this blog to share what I know and what I was learning about personal finance. Along the way I’ve met and found many blogging friends. Please feel free to connect with me on the Beating Broke accounts: Twitter and Facebook.

You can also connect with me personally at Novelnaut, Thatedeguy, Shane Ede, and my personal Twitter.

Luckily, we’re usually pretty good at talking about money with each other. Don’t get me wrong. There’s plenty of room for improvement. But, we’re good about not getting into any heated arguments with each other, and being able to figure out where we’ve gone wrong and correcting it.

Luckily, we’re usually pretty good at talking about money with each other. Don’t get me wrong. There’s plenty of room for improvement. But, we’re good about not getting into any heated arguments with each other, and being able to figure out where we’ve gone wrong and correcting it. Start by shopping around. Just because your optometrist is your eye doctor doesn’t mean you need to purchase all of your eye related devices there. The doctor already has gotten paid for the visit. No other compensation for their time and the visit are necessary. Most towns will have at least two optometrists, and bigger cities will likely have 10-20 or more. Bigger cities may also have at least one of the new discount eyeglasses stores that have been popping up recently. Take your prescription home, then call a few of them and ask about prices for the eyeglasses you need.

Start by shopping around. Just because your optometrist is your eye doctor doesn’t mean you need to purchase all of your eye related devices there. The doctor already has gotten paid for the visit. No other compensation for their time and the visit are necessary. Most towns will have at least two optometrists, and bigger cities will likely have 10-20 or more. Bigger cities may also have at least one of the new discount eyeglasses stores that have been popping up recently. Take your prescription home, then call a few of them and ask about prices for the eyeglasses you need.